Are You Training Hard… or Training Into the Ground?

When training stress outpaces recovery, the immune system can reflect strain before performance declines. Here’s what this long-term immune marker reveals.

What do your workouts have to do with inflammation, recovery, and biological aging?

You’re training consistently, hitting your targets, looking good. Compliments start coming in.

You’re also exhausted - but who cares? Isn’t that normal when you’re exercising seriously?

“Motivation doesn’t matter. Discipline does,” the slogans on social media shout at you - push harder, be consistent, don’t slow down. And most of the time, that mindset works. At least on the surface.

The problem is that discipline doesn’t automatically mean recovery. When training stress keeps piling up, and recovery doesn’t fully catch up, the cost isn’t just feeling tired. The body starts carrying that stress in other ways. Every hard session triggers inflammation. In the short term, that’s part of how adaptation happens. But when the stress is repeated without enough recovery, inflammation doesn’t fully resolve. It lingers. It becomes chronic. That shift doesn’t always show up in your pace, your strength, or how you look. It shows up in how the immune system is behaving over time and that state is closely linked to accelerated biological aging.

Most people never see this happening. Not because they’re careless, but because the tools we usually rely on are built to catch acute problems, not the slow accumulation of immune stress that builds across weeks and months.

But what if you had a way to track that longer-term immune resilience before performance drops?

Overtraining isn’t just “being tired”

Most people never see this happening. Not because they’re careless, but because the tools we usually rely on are built to catch acute problems, not the slow accumulation of immune stress that builds across weeks and months.

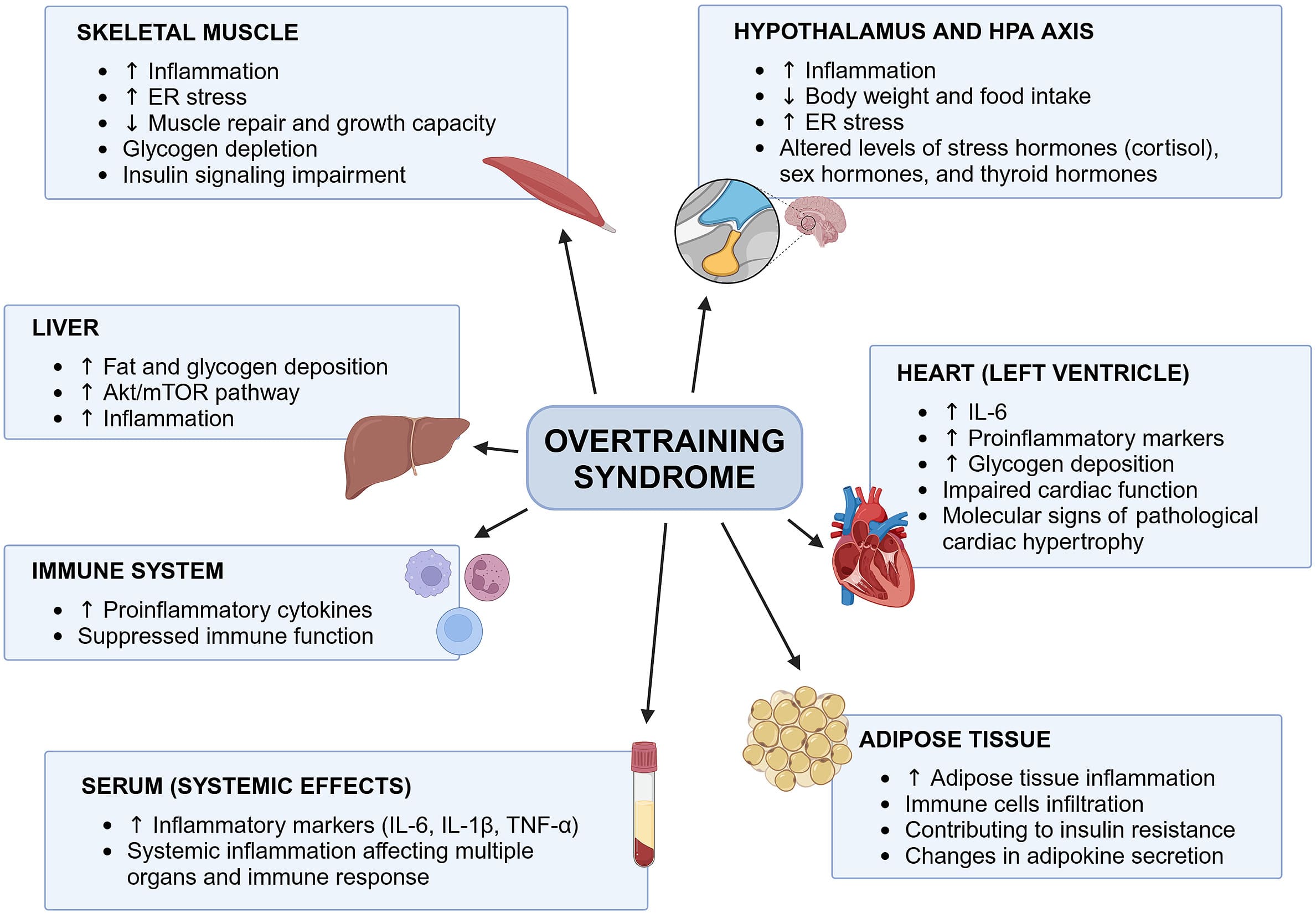

As we know, training creates micro-damage. It’s completely normal because that’s how the process of muscle growing and adaptation happens. But when training stress builds up without enough recovery, the body can shift from short-term inflammation, which is generally useful, to chronic, systemic inflammation, the one we want to avoid. Over time, such a pattern can contribute to a spectrum that looks like:

→ Functional overreaching: short-term fatigue that improves after a few days of rest.

→ Nonfunctional overreaching: longer fatigue + performance decline that can take weeks to recover from.

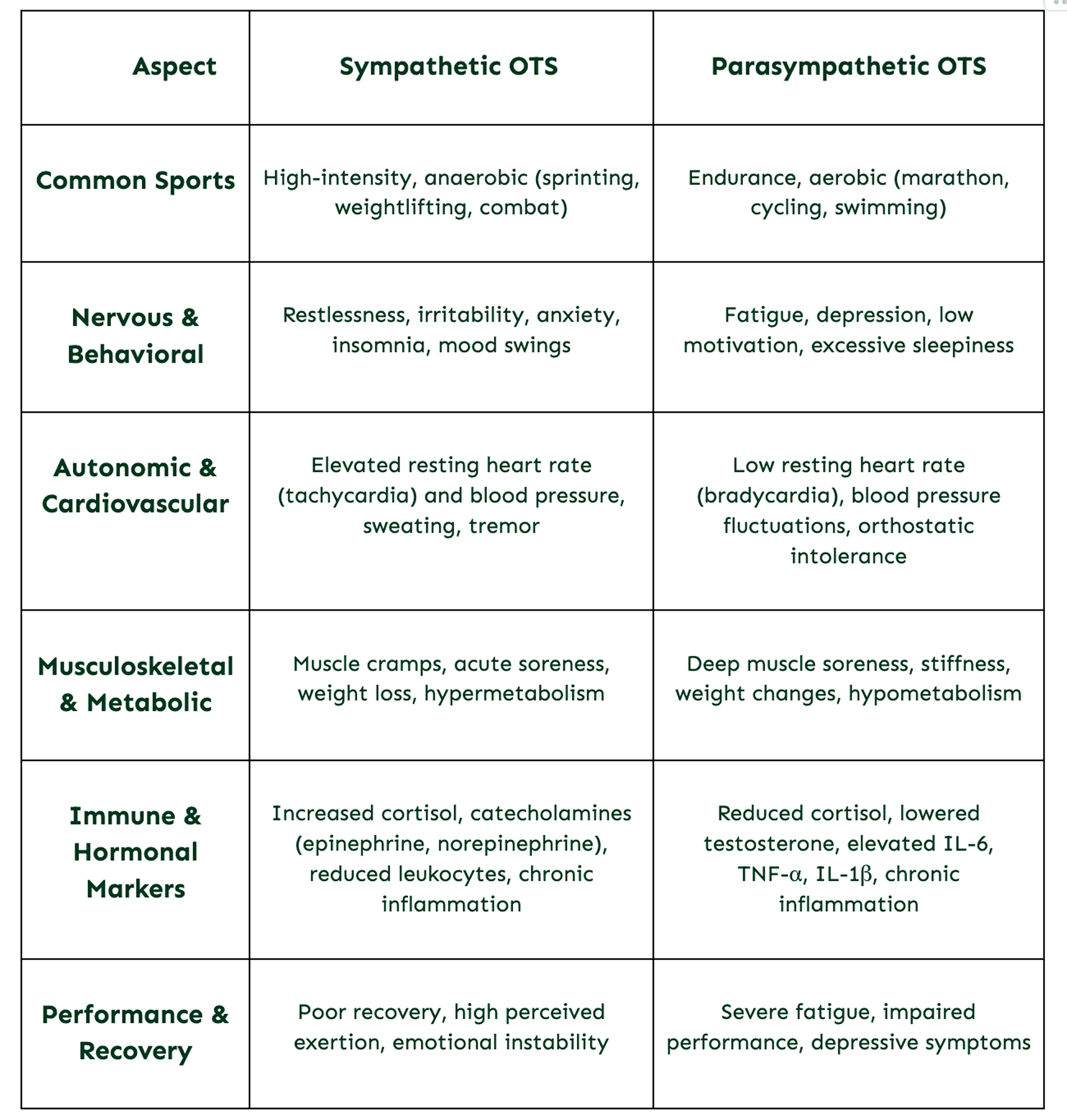

→ Overtraining syndrome: a deeper, system-wide maladaptation that can last months and often comes with mood changes, immune suppression, and neuroendocrine imbalance.

In other words, the body is meant to “bounce back” from physical load. Overtraining is what happens when it stops doing so the way it once did.

Why is overtraining hard to spot early?

Nonfunctional overreaching and overtraining syndrome can look the same at the beginning: fatigue, low motivation, slower sessions, disrupted sleep, soreness that won’t go away.

The diagnosis often only becomes clear in hindsight, based on how long it takes to return to baseline. And it’s not rare:

→ Roughly 10% of endurance athletes experience these issues in a single season

→ Over 60% of elite runners report at least one episode during their career

→ Recurrence can be high - in one report, 91% of affected swimmers experienced it again later

Once overtraining syndrome sets in, recovery can be slow and unpredictable, which is why prevention and early detection matter so much.

The inflammation link: the cytokine hypothesis

One of the strongest explanations for overtraining syndrome is the cytokine hypothesis.

If we are to break it down, here is what it means:

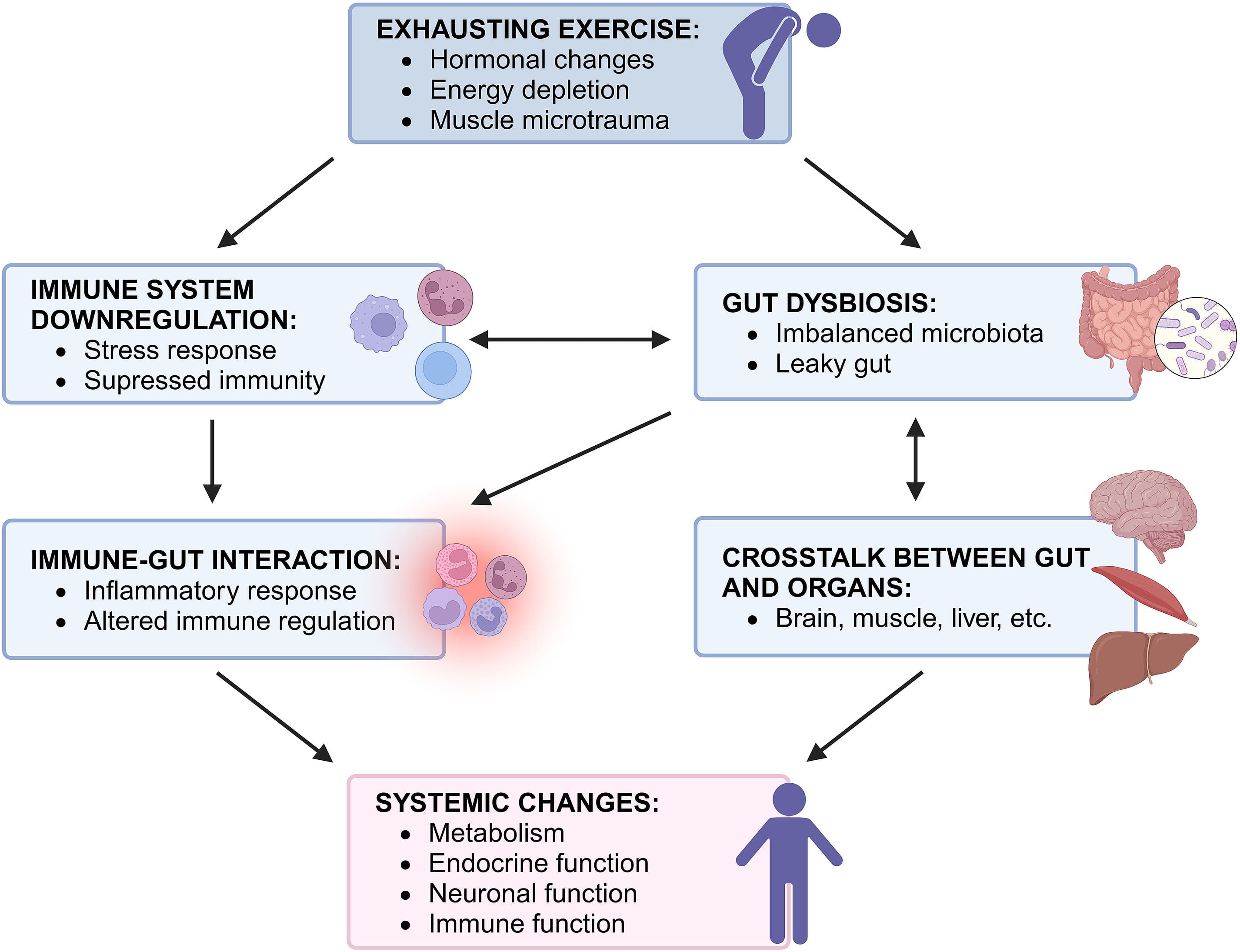

→ Hard training creates tissue stress and micro-trauma (again, generally good).

→ If stress is repeated without enough recovery, the immune system stays activated.

→ Stressed tissue releases signals (including damage-associated molecular patterns) that keep the immune response “on.”

→ Pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α stay elevated, which can push inflammation from local to systemic.

The cytokine hypothesis can manifest as what researchers call “sickness behavior”: fatigue, low mood, low motivation. In such a state, your body shifts resources toward immune activity, which inevitably affects metabolism and recovery capacity. When this response is short-term, it is protective. When it becomes prolonged, it can start to work against the body instead.

Why “normal” inflammation markers do not tell the whole story?

Markers like CRP are helpful for acute inflammation and infection, but they often fail to capture the subtle, long-term immune shifts that accumulate with unresolved training stress.

That’s why looking at something that reflects the immune system over weeks (not days) can provide far more context.

Measuring Long-Term Recovery with GlycanAge

IgG is one of the main antibody types in the blood, and it carries tiny sugar structures called glycans.

Changes in these glycans reflect the immune system’s inflammatory balance over time, acting more like a multi-week record than a daily snapshot.

That’s what GlycanAge analyzes: glycan structures attached to IgG antibodies, summarized into glycan indexes.

→ Glycan Mature and Glycan Bisection track more pro-inflammatory structures.

Higher levels suggest IgG has lost protective sugars, linked to higher systemic inflammation and accelerated biological aging.

→ Glycan Youth and Glycan Shield track more anti-inflammatory (protective) structures.

Higher levels suggest IgG is richer in protective features like galactose and sialic acid, linked to better immune regulation.

Think of it like this: acute markers can tell you what’s happening today. IgG glycans can reflect the trend your immune system has been living in for weeks or months.

The U-shaped story: exercise can help… until it doesn’t

Research suggests that there is a U-shaped relationship between exercise intensity and IgG glycosylation.

It means that:

→ Too little activity can be associated with less favorable immune aging patterns.

→ Moderate, regular activity is associated with a more favorable profile.

→ Chronic extreme training load can push the immune system in an unfavorable direction again.

In one study, people doing regular moderate activity had GlycanAge values averaging about 7.4 years younger than inactive individuals. In women, the difference was even larger. Moderately active females showed biological ages nearly 10 years younger than inactive women.

This could easily lead to the conclusion that more exercise is always better. Here’s the catch:

Professional athletes exposed to sustained high-load training tended to show GlycanAge scores about 7.6 years older than moderately active individuals. This effect was especially pronounced in elite female athletes, where biological age could appear up to 20 years older than moderately active women, likely influenced by heavy training, hormonal shifts, and low energy availability (Šimunić-Briški et al., 2023).

The timing insight: adaptations may show up after recovery

A key takeaway from a longitudinal intervention is that even intense training can support positive immune changes, given that recovery is real (Tijardović et al., 2019).

Participants did:

→ 6 weeks of high-intensity repeated sprint training

→ followed by 4 weeks of recovery

The most meaningful anti-inflammatory glycan changes became clear after the recovery phase, not at the peak of training. The glycan analysis showed:

→ a reduction in pro-inflammatory G0 (agalactosylated) glycans (captured by the Glycan Mature index)

→ and an increase in protective structures like G2 (digalactosylated) and S1 (monosialylated) glycans (captured by Glycan Youth and Glycan Shield)

That’s why it’s important to remember that while the body may be “doing the work” during training, measurable immune benefits often show up only once recovery truly happens.

A real-life example: when “healthy habits” weren’t enough

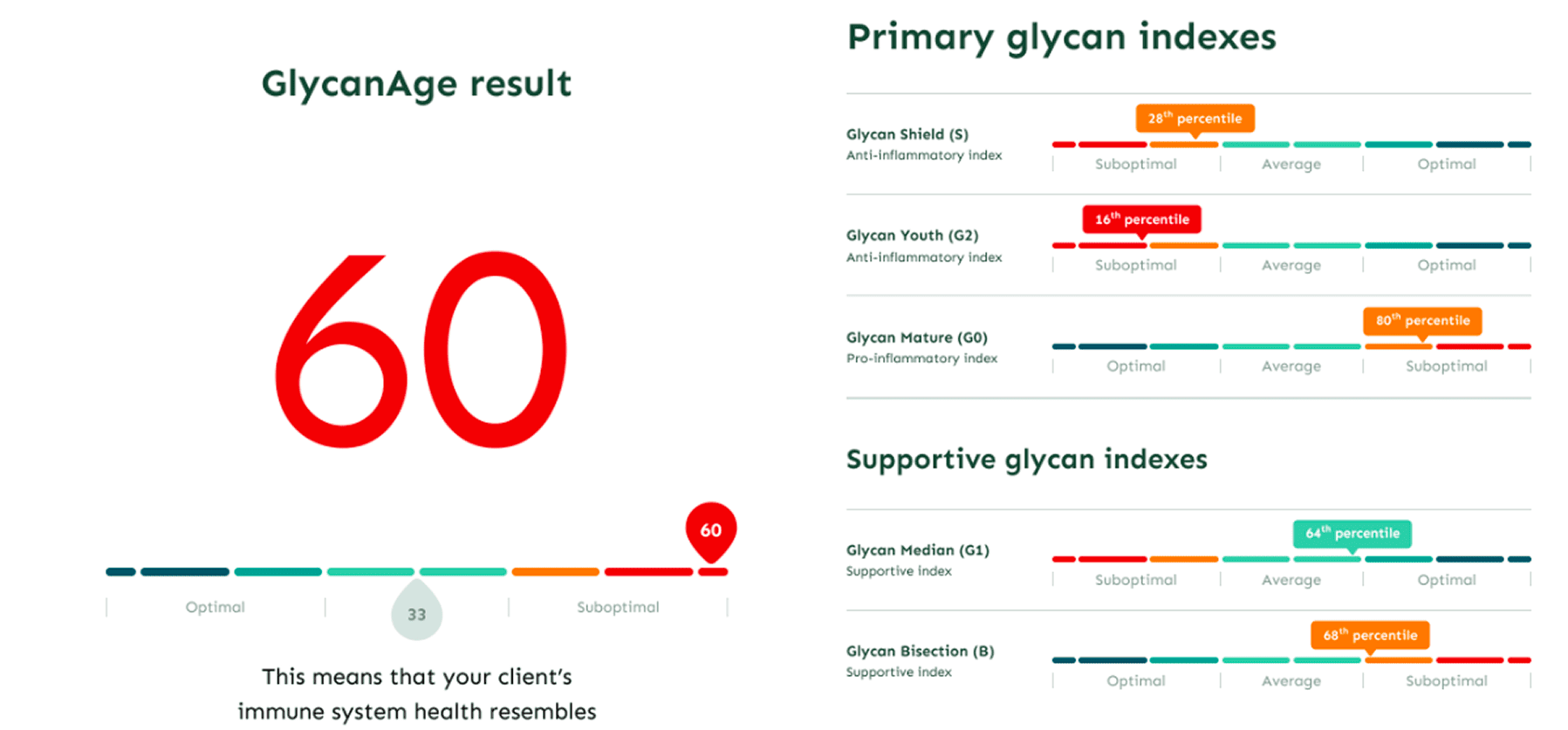

A 33-year-old amateur male athlete tested GlycanAge one month into an intensive marathon training block.

Training included:

→ 50–70 km/week of running

→ plus resistance training and HIIT

Even with a healthy diet and a structured sleep routine, his GlycanAge was 60, which was 27 years older than his chronological age.

His glycan profile showed low anti-inflammatory capacity (low Glycan Shield and Glycan Youth percentiles) and elevated pro-inflammatory markers (high Glycan Mature and Glycan Bisection). This aligned with higher perceived stress.

His sex hormone panel was also consistent with physiological exhaustion: bioavailable testosterone, free testosterone, and DHEA were in the lower range, which is unexpectedly low for a young, highly active male typically expected to show peak hormonal function.

The point isn’t that training is inherently bad. Cumulative stress can still show up biologically, even when life looks disciplined, and it can flag risk before a full breakdown happens.

So what can you do with this information?

Overtraining syndrome has no definitive “quick fix” beyond rest and time, which is why early detection is so valuable.

GlycanAge isn’t meant to replace how you feel, your performance data, or tools like HRV. It can add a biochemical layer, a stable view of how your immune system has been responding over the past several weeks.

For active people, that can support three practical goals:

→ Detect early warning signs: spot rising systemic inflammation before performance drops.

→ Guide recovery more objectively: it’s easier to prioritize rest when you can see the biology behind it.

→ Track whether changes are working: since IgG glycans can respond to lifestyle and therapeutic interventions, repeated testing can help you evaluate whether your strategy is improving the inflammatory balance.

Bottom line

We often expect training to make us look fit and feel strong, which can often push us to the extremes when trying to achieve those goals. However, when stress quietly outpaces recovery, the immune system can start telling a different story, often before it shows up in pace, power, or performance.

GlycanAge, by measuring IgG glycans, offers a longer-term perspective into that story, reflecting how the immune system has been responding over weeks. When used alongside your symptoms, training data, and other markers, tracking IgG glycans can help you manage training load more precisely and protect both performance and long-term health.

References

Paton B, Suarez M, Herrero P, Canela N. Glycosylation biomarkers associated with age-related diseases and current methods for glycan analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11):5788. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115788

Krištić J, Lauc G, Pezer M. Immunoglobulin G glycans – Biomarkers and molecular effectors of aging. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2022 Oct 1;535:30–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2022.08.006

Birukov A, Plavša B, Eichelmann F, Kuxhaus O, Hoshi R A, Rudman N, et al. Immunoglobulin G N-glycosylation signatures in incident type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. 2022 Nov 1;45(11):2729–2736. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-0833

Kreher J B, Schwartz J B. Overtraining syndrome: A practical guide. Sports Health. 2012;4(2):128–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1941738111434406

Smith L L. Cytokine hypothesis of overtraining: A physiological adaptation to excessive stress? Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(2):317–331. PMID: 10694113

Armstrong L E, Bergeron M F, Lee E C, Mershon J E, Armstrong E M. Overtraining syndrome as a complex systems phenomenon. Front Net Physiol. 2022;1. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnetp.2021.794392

Meeusen R, Duclos M, Foster C, Fry A, Gleeson M, Nieman D, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: Joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(1):186–205. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318279a10a

Kuipers H, Keizer H A. Overtraining in elite athletes: Review and directions for the future. Sports Med. 1988;6:79–92. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-198806020-00003

Fiala O, Hanzlova M, Borska L, Fiala Z, Holmannova D. Beyond physical exhaustion: Understanding overtraining syndrome through the lens of molecular mechanisms and clinical manifestation. Sports Med Health Sci. 2025;7(4):237–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smhs.2025.01.006

Cheng A J, Jude B, Lanner J T. Intramuscular mechanisms of overtraining. Redox Biol. 2020 Aug;35:101480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2020.101480

Deriš H, Tominac P, Vučković F, Briški N, Astrup A, Blaak E E, et al. Effects of low-calorie and different weight-maintenance diets on IgG glycome composition. Front Immunol. 2022;13:995186. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.995186

Jurić J, Kohrt W M, Kifer D, Gavin K M, Pezer M, Nigrovic P A, et al. Effects of estradiol on biological age measured using the glycan age index. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(19):19756–19765. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.104060

Šimunić-Briški N, Dukarić V, Očić M, Madžar T, Vinicki M, Frkatović-Hodžić A, et al. Regular moderate physical exercise decreases GlycanAge index of biological age and reduces inflammatory potential of Immunoglobulin G. Glycoconjugate J. 2023;41(5):67–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10719-023-10144-5

Tijardović M, Marijančević D, Bok D, Kifer D, Lauc G, Gornik O, Keser T. Intense physical exercise induces an anti-inflammatory change in IgG N-glycosylation profile. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1522. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.01522