Burning the right kind of fat does not only look good on the outside – it reverts the inner mechanics of the damage caused by obesity.

The world’s focus has been fixated on a certain pandemic for many months. However, there is another pandemic that we have been fighting for a much longer time: obesity. As much as 13% of the world’s adult population is overweight, including an increasing percentage of young adults. We follow an unfortunate trend that does not seem to be slowing down.

Why should the obesity pandemic alarm us?

We all heard it is bad for our health to be obese, but few of us know exactly why. To explain this, we first must answer what it means to be overweight, and the key to the answer lies not only in excess fat but also in the type of it.

There are two different types of fat: The one that is under your skin, called subcutaneous, is the layer of fat you can pinch with your fingers. This kind of fat makes up around 90% of our total body fat, and it creates curves that shape our figure. It is a common misconception that any kind of fat is bad. Plus size does not automatically equal bad health. In fact, the presence of subcutaneous fat is crucial for our health because it stores energy and regulates hormones. The problems arise when there is such excess of it that it adds a substantial amount of weight onto the body, increasing pressure on the skeletal system. Over time, this can lead to problems with multiple joints, mostly hips and knees.

However, as the saying goes: it is not what is outside but what is inside that matters. The other type of fat, the silent killer, is hidden beyond our reach, and it is called visceral fat (dubbed after the Latin word for gut, viscera). It makes up only around 10% of our total body fat. Still, its placement is crucial: deserving of its ”beer belly” nickname, visceral fat accumulates in the belly region. This allows scientists to approximate its amount through waist circumference and predict the health risk it poses. Visceral fat is such a health threat because it surrounds the inner organs and makes it hard for them to function well, resulting in a heightened risk of heart disease, dementia, asthma, and even certain types of cancer (breast and colorectal).

Sadly, obesity has been spreading among the young at an alarming rate. This leads to the early onset of health issues usually linked with old age. Even though these people are young, their bodies act older than they should be.

Can we reverse the effects of obesity?

To manage obesity, we can lose excess weight and diminish the amount of fat stored in our body. However, the question remains: Does this also revert our body’s biological age, or is the damage irreversible?

It is finally time for this article to bring you good news, as the answer to this seems to be “yes!” And it is explained by none other than glycans, sugary sweet molecules that have revealed so much new information to the scientific world in the past couple of decades.

Glycans have been a mystery for a long time, as they are much harder to study than other molecules such as DNA or proteins. But little by little, science has progressed enough that we can now even go so far as to look at a person’s glycans and determine their body’s biological age so precisely that other methods can hardly compare!

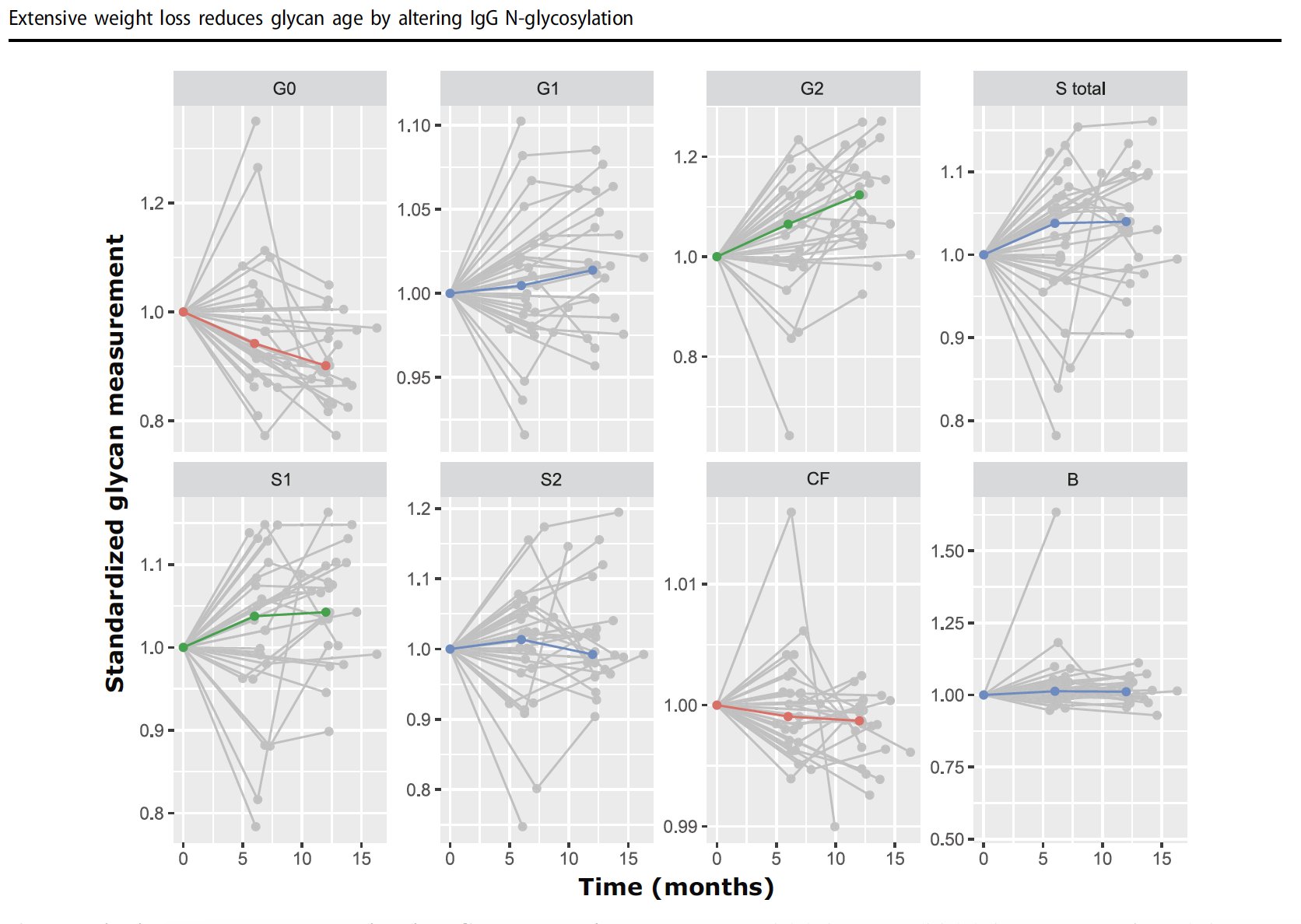

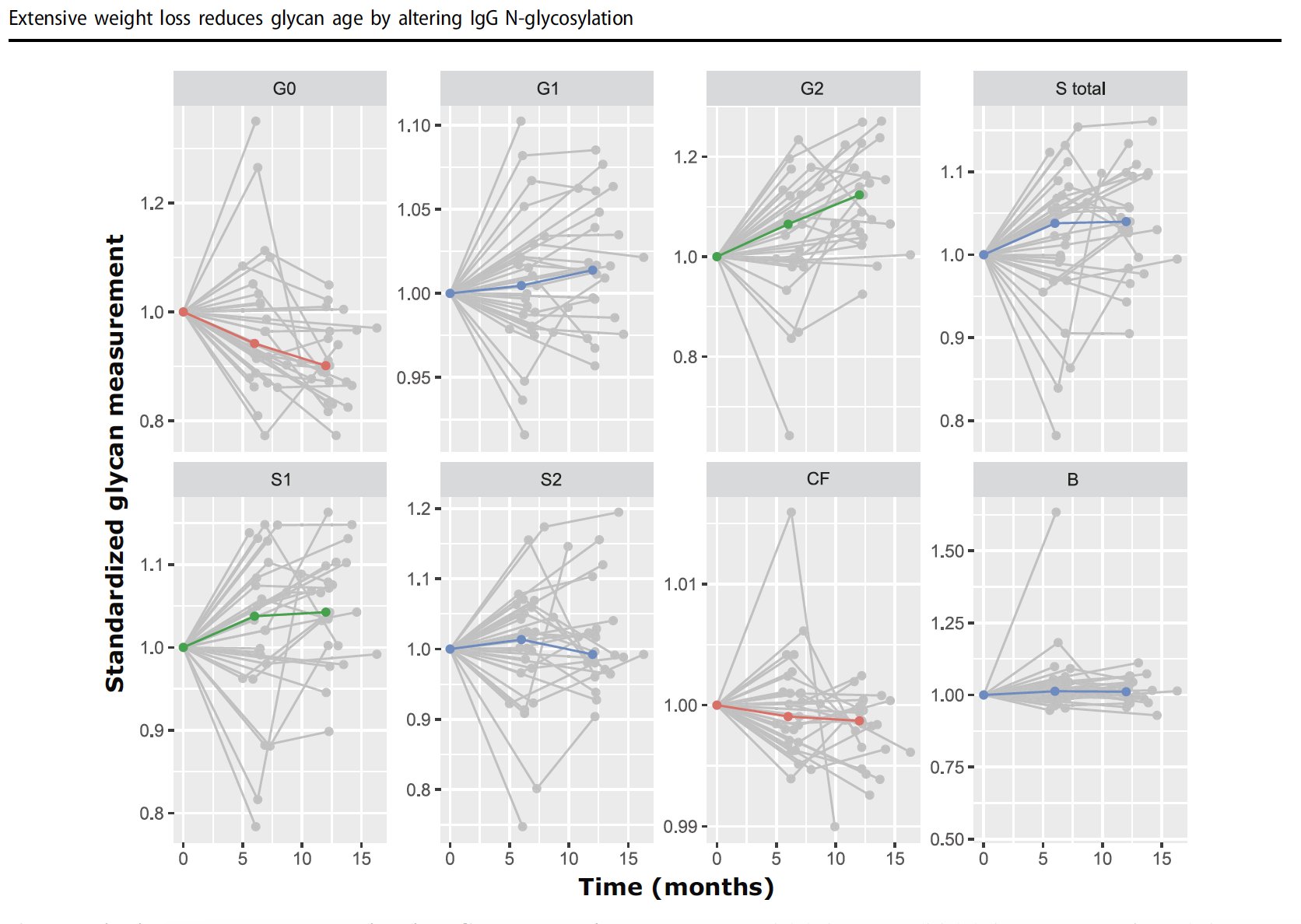

Obese people’s glycans confirm that their bodies are, in most cases, older than their chronological age (birth years). Our team recently went one step further and investigated what happens when obese people lose weight, and the answer was quite exciting: their biological age decreased! This finding implies that the internal damage caused by obesity is possibly entirely reversible.

If you find that your BMI and waist circumference label you as an obese individual and all you’ve been searching for is a good motivator to act, this is your sign. Weight loss can also help you lose a couple of years of biological age – it’s scientifically proven.

Other articles you may like:

Health

HealthProf Azra Raza's Lecture for The Human Glycome Project Researchers

Azra Raza is an oncologist, and professor of medicine, and director of the Myelodysplastic Syndrome Center at Columbia University, New York. She has dedicated almost her entire life to fighting cancer and discovering ways to prevent it by detecting the first cancer cell in the human body.

![]()

By The GlycanAge Team

Health

HealthWhat Are Vaccines Doing to Our Bodies, and Could Sugars Make the Vaccines Better?

A considerable expansion in glycomics capabilities is required to fully exploit protein glycosylation for the development of new vaccines.

By Tea Petrovic

By Tea Petrovic

By Tea Petrovic