Does Heat Make Inflammation Worse? An In-Depth Look at the Relationship

Is heat good for inflammation? Should you use ice or heat for inflammation? Click here to find out.

Inflammation is the body's natural response to injury, infection, or irritation, and it serves as a crucial part of the healing process. It is characterised by redness, swelling, pain, and sometimes loss of function in the affected area.

Heat is a common environmental factor that can influence various physiological processes in the body. However, the question of whether heat causes inflammation is still a subject of debate.

Does heat cause inflammation? In this article, we will delve into the relationship between heat and inflammation, explore the potential mechanisms involved, and discuss when to use ice vs heat therapy to reduce inflammation.

Is Heat Bad For Inflammation?

Thermoregulation and Inflammation

The human body has a sophisticated thermoregulatory system to maintain core body temperature within a narrow range. When exposed to high temperatures, the body can experience heat stress, which may lead to an inflammatory response. The underlying mechanism is thought to involve the activation of heat-shock proteins (HSPs) in response to cellular stress.

The human body has a sophisticated thermoregulatory system to maintain core body temperature within a narrow range. When exposed to high temperatures, the body can experience heat stress, which may lead to an inflammatory response. The underlying mechanism is thought to involve the activation of heat-shock proteins (HSPs) in response to cellular stress.

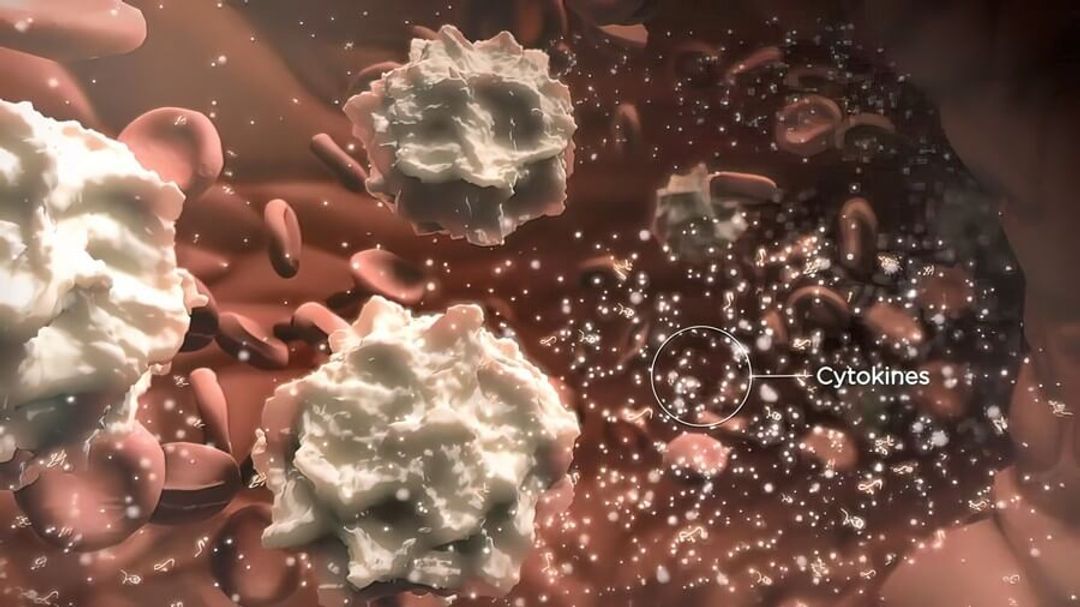

HSPs are molecular chaperones that help maintain protein stability and function during stress. They are also involved in the inflammatory response, as they can interact with immune cells and stimulate the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

One study found that exposure to heat stress increased the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) in a dose and time-dependent manner in rats [1].

However, this study focused on extreme heat exposure, and it remains unclear whether moderate heat exposure would elicit the same inflammatory response.

Heat Therapy and Inflammation

Heat therapy, also known as thermotherapy, involves applying heat to the body to alleviate pain and promote healing. It is a common treatment for various musculoskeletal conditions, such as arthritis, muscle strains, and joint stiffness. Some studies have found that heat therapy can help reduce inflammation in specific cases.

Heat therapy, also known as thermotherapy, involves applying heat to the body to alleviate pain and promote healing. It is a common treatment for various musculoskeletal conditions, such as arthritis, muscle strains, and joint stiffness. Some studies have found that heat therapy can help reduce inflammation in specific cases.

For example, a study by Petrofsky et al. found that applying heat to the knee joint for 30 minutes led to a significant decrease in pro-inflammatory cytokines and an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines in patients with knee osteoarthritis [2].

Another study found that heat therapy reduced inflammation and pain in patients with acute low back pain [3].

These findings suggest that heat therapy may have an anti-inflammatory effect in certain conditions.

Heat and Inflammation in Exercise

Physical exercise can generate heat in the body, leading to an increase in core body temperature. This heat generation can activate heat-shock proteins and induce an inflammatory response. However, exercise-induced inflammation is generally considered a physiological response that promotes tissue repair and helps the body adapt to the exercise stimulus.

Physical exercise can generate heat in the body, leading to an increase in core body temperature. This heat generation can activate heat-shock proteins and induce an inflammatory response. However, exercise-induced inflammation is generally considered a physiological response that promotes tissue repair and helps the body adapt to the exercise stimulus.

A study by Febbraio et al. found that exercise-induced heat stress increased the production of Hsp72, a heat-shock protein, in the blood of human subjects [4].

This increase in Hsp72 was associated with a reduction in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, suggesting that exercise-induced heat stress might have an anti-inflammatory effect.

It is essential to note that the intensity and duration of exercise may influence the inflammatory response, with moderate-intensity exercise generally associated with a more favourable anti-inflammatory profile.

The Role of TRP Channels in Heat-Induced Inflammation

Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are a family of proteins that act as sensors for various environmental stimuli, including temperature. Some TRP channels, such as TRPV1 and TRPA1, are known to be involved in the sensation of heat and pain. These channels can be activated by heat, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory mediators and the sensation of pain.

Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are a family of proteins that act as sensors for various environmental stimuli, including temperature. Some TRP channels, such as TRPV1 and TRPA1, are known to be involved in the sensation of heat and pain. These channels can be activated by heat, leading to the release of pro-inflammatory mediators and the sensation of pain.

A study by Billeter et al. found that activating a specific protein called TRPV1 played a role in causing inflammation due to heat in a mouse burn injury experiment. When they blocked this protein, there were fewer immune cells and inflammation-causing substances in the injured area [5].

This suggests that these special proteins (TRP channels) may be involved in how heat causes inflammation. However, more research is needed to figure out exactly how this works and if it applies to humans as well.

Heat and Inflammation in Skin Conditions

Heat exposure can exacerbate certain skin conditions characterised by chronic inflammation, such as atopic dermatitis (AD) and psoriasis. In these conditions, heat might contribute to inflammation through several mechanisms, including increased blood flow, activation of itch-related pathways, and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Heat exposure can exacerbate certain skin conditions characterised by chronic inflammation, such as atopic dermatitis (AD) and psoriasis. In these conditions, heat might contribute to inflammation through several mechanisms, including increased blood flow, activation of itch-related pathways, and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

For instance, a 2021 article in The New England Journal of Medicine found that heat exposure increased the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the severity of AD-like symptoms [6].

Another study reported that heat stress worsened psoriasis symptoms in patients and increased the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in skin samples [7].

These findings suggest that heat might contribute to inflammation in certain skin conditions, although the underlying mechanisms are still not fully understood.

Heat and Inflammation: The Role of Diet

Diet can influence the body's inflammatory response, and certain foods might contribute to heat-induced inflammation.

Diet can influence the body's inflammatory response, and certain foods might contribute to heat-induced inflammation.

For example, spicy foods contain capsaicin, a compound that can activate TRPV1 channels and trigger the release of pro-inflammatory mediators. This can result in a sensation of heat and pain, as well as an increase in inflammation in some individuals.

A 2011 study found that consuming a capsaicin-rich diet increased the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the blood of healthy subjects. However, it is important to note that the inflammatory effects of capsaicin might depend on individual sensitivity and the dose consumed [8].

More research is needed to determine the role of diet in heat-induced inflammation.

When To Use Ice Vs Heat For Pain And Inflammation

When it comes to treating pain, either ice or heat can be effective, but their usage depends on the type of injury and the stage of the healing process. Below is a guide to help you decide when to use ice and when to use heat for pain relief.

Use Ice for Acute Injuries

For acute injuries, such as sprains, strains, bruises, and sudden-onset pain, ice is generally the preferred treatment. It helps in the following ways:

-

Reducing inflammation: Ice constricts blood vessels, reducing blood flow and inflammation in the injured area.

Reducing inflammation: Ice constricts blood vessels, reducing blood flow and inflammation in the injured area. -

Alleviating pain: Cold temperatures can numb the pain and alleviate discomfort.

-

Minimising tissue damage: By limiting inflammation and swelling, ice can help reduce tissue damage in the affected area.

For the best results, apply ice as soon as possible after the injury occurs. Use an ice pack, a bag of frozen vegetables, or a cold compress, and wrap it in a thin cloth to protect your skin. Apply the ice for 15-20 minutes at a time, and wait at least 30 minutes between applications.

Use Heat for Chronic Pain and Muscle Tension

Heat therapy is typically used for chronic pain or conditions such as arthritis, muscle stiffness, and muscle spasms. Heat is beneficial because it:

-

Increases blood flow: Heat dilates blood vessels, increasing blood flow to the affected area, which can promote healing and reduce muscle stiffness.

Increases blood flow: Heat dilates blood vessels, increasing blood flow to the affected area, which can promote healing and reduce muscle stiffness. -

Relaxes muscles: Warm temperatures help to relax tight muscles and reduce muscle spasms, providing relief from pain and discomfort.

-

Decreases joint stiffness: Heat can help to improve the range of motion and reduce joint stiffness in conditions like arthritis.

For heat therapy, you can use a heating pad, a hot water bottle, a warm towel, or take a warm bath or shower. Apply heat for 15-20 minutes at a time, ensuring that the temperature is comfortable and not too hot to avoid burns.

Use Ice then Heat

In some cases, you may transition from ice to heat therapy as the injury heals. For example, during the first 48-72 hours after an injury, you may use ice to reduce inflammation and swelling. Once the acute inflammation has subsided, you can switch to heat therapy to promote healing, improve flexibility, and reduce muscle stiffness.

Always consult a healthcare professional for personalised advice on treating injuries and pain. They can provide guidance on the best course of action based on the nature of your injury and your individual circumstances.

How To Combat Heat To Reduce Inflammation

To combat heat-induced inflammation, you can take several preventive and therapeutic measures. Consider following these steps:

-

Avoid excessive heat exposure and direct sunlight.

Avoid excessive heat exposure and direct sunlight. -

Stay hydrated by drinking plenty of fluids.

-

Use cool compresses or cold packs on affected areas.

-

Take over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medications as needed.

-

Elevate the affected area, if applicable.

-

Rest and avoid activities that may worsen inflammation.

-

Apply aloe vera gel on heat-related skin conditions.

-

Consume a healthy, anti-inflammatory diet.

-

Maintain good skincare practices.

-

Consult a healthcare professional for severe or persistent inflammation.

Take Care Of Your Health With GlycanAge

The relationship between heat and inflammation is complex and depends on various factors, such as the intensity and duration of heat exposure, the presence of underlying conditions, and individual susceptibility.

While extreme heat exposure can cause an inflammatory response, moderate heat exposure, as seen in heat therapy and exercise, might have anti-inflammatory effects.

TRP channels, heat-shock proteins, and dietary factors might all play a role in heat-induced inflammation. Further research is needed to understand the precise mechanisms involved and to develop targeted interventions for individuals susceptible to heat-induced inflammation.

Symptoms of chronic inflammation and associated diseases often only manifest once they have progressed to later, more problematic stages. The GlycanAge biological age test can accurately predict the risk for future health conditions long before they have developed within the body.

The extent of chronic inflammation within your system is directly linked to lifestyle choices. GlycanAge measures the extent of chronic inflammation and thus determines your biological age (the true age of your cells, tissues, and organs). This vital information can empower you to make appropriate changes to your lifestyle to reverse inflammation and reduce your biological age over time.

The extent of chronic inflammation within your system is directly linked to lifestyle choices. GlycanAge measures the extent of chronic inflammation and thus determines your biological age (the true age of your cells, tissues, and organs). This vital information can empower you to make appropriate changes to your lifestyle to reverse inflammation and reduce your biological age over time.

A single test is recommended if you are beginning your wellness journey and want to discover your biological age. Two tests can help you measure how effectively your health has improved and how much you’ve reversed your biological age in response to lifestyle interventions over a period of time. A custom plan is best for biohackers or those invested in improving their health in the long term.

Affordable payment plans are available as part of each package. You’ll also receive a complimentary 1-to-1 consultation with a scientist and/or a qualified healthcare professional to help you understand your results and devise a personalised action plan to help delay and reverse the ageing process.

If you’re ready to take control of your health, order your GlycanAge biological age test today.

References

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15665732/

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23933600/

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16641776/

-

https://research.monash.edu/en/publications/exercise-induces-hepatosplanchnic-release-of-heat-shock-protein-7

-

https://journals.lww.com/annalsofsurgery/Abstract/2014/02000/Transient_Receptor_Potential_Ion_Channels_.7.aspx

-

https://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMra2023911

-

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8974693/

-

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21487045/